İngilis dili müəllimləri üçün: İbtidai siniflər üçün üsullar (III fəsil)

CHAPTER THREE

MORE TECHNIQUES

FOR BEGINNERS’

CLASSES

We have seen (in Chapter 2) that understanding the meaning is only the first step in learning a word. It is a step that should take as little time as possible. Much more time should be given to other activities – activities which require students to use the new words for real communication.

Let’s assume that we have shown our students the meanings of all the new words in our sample textbook lesson ( boy, girl, person, room, wall, floor, window, door, clock, picture) . Some meanings have been shown by pictures. For others (wall, floor, window, door, clock) we have pointed to something in our own classroom which is named by the English word. The students have heard and seen each of the words; they have copied the new vocabulary into their notebooks. In addition, they have used three of the new words (boy, girl, and person) in communication activities, as described in Chapter 2.

Now we are ready to engage the class in other experiences requiring the use of the new words. Here are a few of many possibilities:

1. The teacher introduces a very short dialog in which members of the class are identified according to their location (near the door/window/clock, etc. ).

Teacher: I’m thinking of a boy. He’s near the clock.

A Student: Are you thinking of ____?

(After the dialog has been introduced by the teacher, it is used as follows: One student thinks of a classmate and mentions his or her location.The other students guess.)

2. The dialog is changed to include a review of colors and clothing (if words for these have been taught – and if the students are not wearing uniforms).

Teacher: I’m thinking of a girl in a blue dress.

A Student: Is she near the window?

Teacher: No. She’s near the door.

A Student: Are you thinking of _____?

3. Various students are asked to perform actions which demonstrate their understanding of the vocabulary – particularly door, window, wall, and clock. Members of the class (a few at a time) are asked to perform such actions as the following:

Go to the door. Then go to a window.

Touch the wall under the clock.

Go back to your seats.

When the students have been at their seats for a long time and need a little physical activity, a good way to encourage learning of the new vocabulary words is to put them into simple commands. If the words go, touch, and under have not yet been taught, the meanings should be demonstrated by the teacher. Or the command which uses the unknown word may be spoken quietly – in the students’ language – to two or three students who will perform the action first. Then the teacher repeats the command in English for the other students to hear and obey.

4. To put the word floor into a communication experience, there is a simple command that all members of the class can obey while sitting at their desks: ”Touch the floor.” This command can then be used for introducing additional words. One way of doing this is for the teacher to ask two or three students to occupy chairs at the front of the room, with their backs to the rest of the class. The teacher then asks them (first softly in their own language, then aloud in English) to demonstrate each of the following:

Touch the floor with one hand.

Touch the floor with both hands.

Touch the floor with your right hand.

Touch the floor under your chair with your right hand.

Notice that left is not introduced immediately after the word right. Even among adult native speakers of English, there are many who continue to confuse right with left. To reduce the chance of confusion it is usually wise to teach right thoroughly before introducing its opposite, left. (If – as often happens – the textbook presents both right and left in the same lesson, we can at least give more of the class time to the learning of right. Then, in a later lesson, we can come back to left for special practice.)

After several students have demonstrated comprehension of the new vocabulary by responding to the teacher’s commands, individual members of the class take the role of the teacher. Each gives the same commands, which have been demonstrated, and classmates perform the actions. Besides offering practice in the use of the new vocabulary, the activity helps to keep students’ minds alert.

WHY COMMANDS ARE USEFUL IN VOCABULARY CLASSES

When we ask students to respond physically to oral commands which use the new words, the activity is very much like what happens when one is learning one’s mother tongue.

Each of us – while learning our own language – heard commands and obeyed them for many months before we spoke a single word. Even after we started to talk, it was a long time before we mastered the words and constructions that we heard from adults. Nevertheless, we could understand the adults’ commands; we could and did respond to commands like “Go to your toy box and get your new fire engine – the one with the wheel that you broke yesterday – and take it to Grandpa.”

Children have frequent experiences in obeying commands during the early years of learning the mother tongue.Those experiences appear to play an important part in the learning of vocabulary.Comparable experiences should be provided in the second- language classroom for students of all ages.

We have been considering words for things and persons in the classroom – the kinds of words generally found in textbooks for beginners in English. We have suggested ways of making such words appear necessary and important. We have mentioned the value of giving students the English word after they have begun to think about the object or action or situation which the word represents.

When students have observed an action – touching, for example – and have wondered what the action is called in English, it is not diffucult to teach them the word touch. For mastery of the word,we can then ask the class to obey simple commands that contain touch; the commands are given first by the teacher, then by selected students.

USING REAL OBJECTS FOR VOCABULARY TEACHING

For helping students understand the meaning of a word, we often find that a picture is useful, if it is big enough to be seen by all members of the class. But real objects are better than pictures whenever we have them in the classroom. When there are real windows, doors, walls, floors, desks, and clocks in the classroom, it is foolish not to use them in our teaching. But in some classes, unfortunately, the students seem never to be asked to look at them, point to them, walk to them, touch them. Only the textbook pictures are used. This is a waste of excellent opportunities. In most cases, a picture of something is less helpful than the thing itself.

There are a few exceptions, however. The exceptions include articles of clothing. Shoes, shirts, skirts, dresses, etc., are usually present in the classroom; but when we show meanings of such words we should be careful about calling attention to clothing which is worn by members of the class. Such attention may make the wearer feel uncomfortable.

This problem does not usually arise with less personal kinds of objects: eyeglasses, sunglasses, wallets (or billfolds), handbags, umbrellas. Several of these can often be found in the classroom; other objects can be brought to class easily enough: a can opener, a pair of scissors, a box of paper clips, a toothbrush, a bar of soap, buttons of many colors and sizes and of various materials. The general recommendation is this: For showing the meaning of an English noun, use the real object whenever possible.

There are exceptions to the recommendation for real objects, however. These exceptions include (1) clothing that members of the class are wearing, and (2) words like man, woman, boy, and girl. In many situations, it seems awkward to point to individual members of the class while saying, “He’s a boy; she’s a girl.” Pictures of persons, or stick figures (drawn by the teacher or a student) are more suitable.

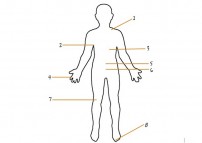

For similar reasons, teachers often prefer to use pictures for introducing words that name parts of the body. The best sort of picture for this purpose is a simple, impersonal line drawing.

Notice that an arrow has been drawn to each part which is to be named, and each arrow is numbered. Notice also that the English names for the parts do not appear on the drawing yet.

On the day when such words are to be learned, the teacher (or a member of the class) makes a large copy of the drawing on the blackboard. The students are given a minute to look at the drawing, and to copy it – and also to wonder what the English words for the parts of the body are.

Now they are ready to learn that arrow 1 points to the head. The teacher says the word and writes it above the arrow beside 1. As each part is named, the student writes the English word on the numbered arrow on his copy of the drawing.

This is the first step toward learning English names for the parts of the body. But it is only the first step. We have not yet created in the student’s mind a feeling of need for each of those English words. We have not convinced him that it is important to learn a new word for something he can already name in his mother tongue. For that purpose, we may again use a series of commands. (Each should begin with please if we wish to demonstrate courtesy while teaching vocabulary.) Commands are given – perhaps first in the students’ language, quietly, to one or two who demonstrate the action. They should be standing with their back to the rest of the class. After the meaning of each meaning command has been shown, the teacher repeats it in English. Groups of students stand and perform the actions. Each action involves a part of the body which is named by one of the new words:

Raise your right hand.

Put your left hand on your head.

Touch your neck with both hands.

Put your hands on your knees.

Put both hands on your shoulder.

Put your right hand on your left knee.

Bend your knees and touch the floor.

Touch the floor near your left foot.

Put both hands on your legs.

Sit down and put your hands on your knees.

For practice in saying the new words, a number of students may be asked to play the teacher’s role, giving the commands. Even those who do not actually say the words, however, benefit from this kind of experience. They have many opportunities to associate familiar actions with the English words that name them. Furthermore, it becomes important to the student to notice whether he hears neck or knee, for example, when a command is given.

OTHER COMMUNICATION EXPERIENCES FOR THE CLASSROOM

There are many other ways to create a communication situation in the classroom, of course. Suppose we have used a picture that shows a head with its various parts: hair, eyes, ears, nose, mouth.Those parts have been named in English; the students have printed the names in their notebooks üith their copies of the picture. Now the stage is set for an experience in which students use those English words to communicate. The activity may go like this:

First the teacher introduces the topic of life on other planets, using a few pictures and (if necessary) a few sentences in the students’ language. The students are then told that they are going to read about a visitor from another planet. Their job is to draw a picture of the visitor, according to the sentences which they are going to read. For example, if they read that the imaginary visitor has two heads, they must draw two heads. No one should look at a classmate’s drawing. They will have five minutes for reading the description and drawing the picture. (If students cannot read English, the description should be read for them by the teacher.)

Each student takes a pencil and a blank sheet of a paper on which to make his drawing. The description of the visitor (which the teacher had previously printed on a large sheet) is taped to the wall, and the students begin the task.

The sentences that describe the visitor may be these:

I have a friend from Mars. My friend has a big head. He has three eyes. He does not have hair. In place of hair, he has five ears. His five ears are on top of his head. His neck is very long. His mouth and his two noses are in his long neck. Please draw a picture of this visitor from Mars.

During the time allowed for this activity, the teacher walks around the room, observing the work of the students. One student is asked to copy his drawing on the blackboard, while the teacher reads the description aloud. The drawing is discussed. Does it fit the description? The teacher’s own drawing (made before class, on a large sheet) is displayed. There is a discussion (in English) of differences between the students’ drawing and the teachers’s model.

For homework, each student may make a different drawing which represents an imagined visitor from another planet – his own idea of such a visitor. He is then to write a description of his visitor (in English) and bring it to class with his drawing. After the descriptions have been corrected by the teacher, each student tries to make a drawing which fits a classmate’s description. His classmate judges the accuracy of the drawing compared with the sentences which describe the visitor.

THE VALUE OF PICTURES THAT STUDENTS DRAW

In several of the techniques which have been mentioned, pictures are made by students. Many teachers like to use pictures the students themselves have made. Such pictures have certain advantages.

1. They cost little or nothing.

2. They are available even in places where no other pictures can be found.

3. They do not require space for storing and filing as pictures from other sources do.

4. Sometimes students who are poor language – learners can draw well. Exercises which require drawing will give such students a chance to win praise, and the praise may help those students learn.

5. When someone has drawn a picture of a scene, he knows the meanings of the English words that the teacher will use while talking about parts of his scene. The meanings are in his mind before he is given the English word. (As we have noted, meanings often come before words in successful learning of vocabulary.)

Fortunately much of the basic vocabulary represents things which are easy to draw – even when the student (or teacher) is not an artist. Most people can draw well enough to show meanings of house, church, tree, flower, cloud, moon, mountain, and star. Even the least artistic teacher can draw pictures to represent the words flag, dish, cup, glass, ladder, and key. If the teacher prefers not to make pictures, there is almost always some member of the class who will enjoy doing so. Young students are especially fond of drawing – particularly when they are permitted to draw on the blackboard.

Here is a way to use students’ artistic talents for the introduction of new vocabulary. Two students who like to draw are asked to go to the blackboard. The teacher explains that these two helpers will draw some pictures for the class, and that the teacher will give the English word for each picture after it has been drawn. Each of the two helpers – working side-by-side – draws a series of pictures, as instructed by the teacher, who whispers directions (in the students’ language if necessary).For example, the teacher’s whispered instructions may be as follows, “two or three trees, a few clouds, the sun, a few birds, a mountain, a house, a ladder against a wall of the house, a tent, a flag on the tent.”

After each of these has been drawn by both helpers, the teacher gives the English word for what was pictured, and it is copied into notebooks by members of the class. When the scene is completed, the helpers, whom we’ll call Paul and Henry, take their seats. Another student is asked to come to the blackboard. His job is point to any part of either picture which is mentioned during the following conversation:

Teacher: I see three clouds in Paul’s picture. (The student at the board points to them.) What do you see?

A member of the class: I see four birds in Henri’s picture. (The student at the board points.)

The conversation is continued, by various students, until all parts of both pictures have been mentioned and pointed to.

The techniques described in this chapter encourage students to use new vocabulary through such activities as the following:

● guessing games in which members of the class are identified by location and by clothing

● actions that are performed in response to commands

● drawing of pictures by students to match English descriptions

● discussions of pictures drawn by members of the class

Such techniques require no special equipment or material, and they give students personal reasons for feeling that English words for familiar objects are good to know.

ACTIVITIES

1. Write a dialog that could introduce a guessing game (similar to 2 on page 22) in which the players use English words for colors, clothing, and parts of the classroom (wall, window, clock, etc.).

2. Write a series of commands (similar to 3 on page 22) that would require students to understand the following words: hand, head, face, ear, neck, back, foot (feet).

3. Write a series of commands which all members of class could obey without leaving their seats. The commands should contain basic vocabulary and require physical actions.

4. It is better to point to the real desks and windows in the classroom than to use a picture of desks and windows for showing meanings of English words. However, some meanings should probably be shown through pictures. In which of the following might it be better to use pictures instead of touching or pointing to examples in the class? Under what circumstances would pictures be preferable: nose, dress, shoes, blackboard, map, clock, watch, leg, wall?

5. Page 25 lists many objects (scissors, buttons, etc.) that can easily be brought to the classroom to show meanings of vocabulary. Add five more available objects to that list.

6. Write a very simple description of an imaginary visitor from another planet. Then write instructions to tell students how to use the description for the picture – drawing on page 27.

7. Draw simple pictures to illustrate meanings of five of the following words: house, tree, flower, sun, moon, star, flag, cat, cup, ladder, wheel, snake, fish.

8. Suppose you have students in your vocabulary class who like to draw pictures. Make a list of ten things you could ask them to draw on the blackboard for a review of English vocabulary. (Include some phrases, like a few clouds above a mountain, a flag on a pole beside a house.)